Photo by S&B Vonlanthen on Unsplash

At the CTTL, we’re focused on using the best of Mind, Brain, and Education Science research to help teachers maximize their effectiveness and guide students toward their greatest potential. Doing that often means addressing what we like to call “Learning Myths”—those traditional bits of teaching wisdom that are often accepted without question, but aren’t always true. We also like to introduce new insight that can change the classroom for the better. In our Learning Myths series, we’ll explore true-or-false statements that affect teacher and student performance; for each, we’ll dive into the details that support the facts, leaving teachers with actionable knowledge that they can put to work right away.

True or False? The emotional and cognitive areas of the brain are highly interlinked, so emotional factors like stress, anxiety, happiness, motivation, and positive relationships need to be considered when thinking about ways to improve learning.

Answer: True. Emotion recruits many of the same areas of the brain used for learning. When a student has a learning experience, emotion and cognition operate seamlessly in the brain. Learning is improved when teachers consider each student’s emotional needs.

When many of us first thought about teaching as a career, it’s likely that we thought of the job as mostly subject-based: we’d become experts in something, and then impart our wisdom onto our students. Voilá! There’s one important piece that we likely didn’t think much about, though: engaging with our students’ emotions.

As a profession, we’re learning more and more about how the brain operates. We now know that cognitive and emotional systems are highly interconnected. Learning is an inherently emotional experience, which means that we can harness positive emotions to help students in the classroom—but we’ve also got to be aware that negative emotions can impede students’ ability to learn.

You’ll often hear talk about a “whole child” approach to education, or the “whole child school experience.” These terms, and the practices behind them, come from a growing recognition that students’ ability to learn is constantly impacted by their surroundings. Physical and mental health, environment, community, relationships, and various kinds of development—social, emotional, and identity—matter too.

If we don’t take those factors into account, we are creating unnecessary barriers to learning. If we do plan education with those factors as part of the necessary ingredients for learning, we can create schools where all students can thrive—in combination with high-quality teachers and effective pedagogy, of course.

So, how do we embrace the emotional factors that help our students learn? Here are some ideas:

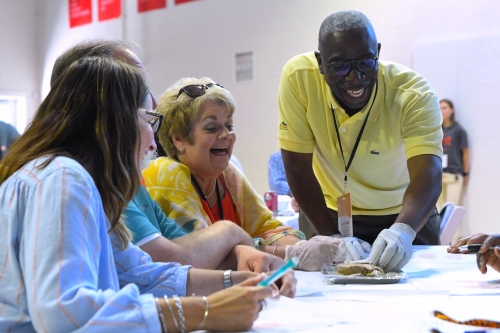

- Remember that relationships really matter in school. Take the time to get to know your students and understand their interests. When they feel seen, they’ll be more connected to you and face fewer obstacles in their learning. University of Ghent professor Richard Ryan puts it this way: “‘My teacher likes me’ is the cheapest intervention in education.”

- Help your students feel that they belong in your classroom and your school. Research from Dr. David Yeager of UT Austin has shown that a simple “belonging intervention” created positive impact on everything from academic measures to involvement in clubs to health visits—especially for first-generation and minority students. It can help mitigate students’ worries that they may not be able to be successful in a given institution, reassuring them instead that everyone struggles at some point—and that they’re in a good place to work through their own struggles. One way to support your students’ sense of belonging: for each one, identify one personal strength and one way in which they add something valuable to the school community. Then, make sure they know that you recognize and celebrate what they bring to the table.

- Simple, but effective: Greet your students by names every day. (You don’t need to make a big production of this; we merely mean that you can use their names as you see them and say hello in your classroom or around the school.) And make sure you’re pronouncing them correctly—mispronouncing one person’s name can actually upset many people in the class. When you say a student’s name correctly, you’re telling them that their relationship with you is important to you. Ideally, every student at your school should hear their name spoken aloud by an adult at least once a day.

- According to Dr. Jack Shonkoff at Harvard, some degree of stress is necessary for building a healthy stress response system (we call this eustress)—but too much can have negative mental and physical health consequences, in addition to decreasing learning potential. To keep stress under control, make sure that you build downtime into the rhythm of your teaching (and the overall school day, which includes a reasonable amount of quality homework). Constant stress with no breaks will wear down your students.

Your students are undergoing intense growth during their school years: physical, social, and emotional. Their relationships with you can be pivotal to their development. Depending on their situations at home, they may actually spend more quality time with you than they do with their parents! This gives you a powerful opportunity to help shape their learning, sense of belonging, and self-regard—and even small changes can make a significant difference.

Here at the CTTL, we love helping teachers bring their best selves to the classroom. Case in point: our newest endeavor, Neuroteach Global, helps teachers infuse their classroom practices with research-informed strategies for student success—in just 3-5 minutes a day, on a variety of devices.