Photo by Daniel Chekalov on Unsplash

Photo by Daniel Chekalov on Unsplash

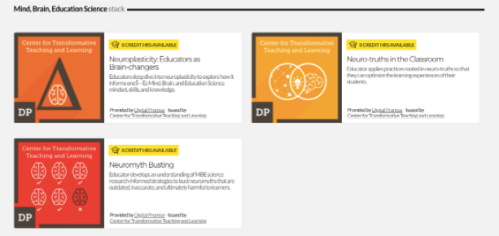

At the CTTL, we’re focused on using the best of Mind, Brain, and Education Science research to help teachers maximize their effectiveness and guide students toward their greatest potential. Doing that often means addressing what we like to call “Learning Myths”—those traditional bits of teaching wisdom that are often accepted without question, but aren’t always true. We also like to introduce new insight that can change the classroom for the better. In our Learning Myths series, we’ll explore true-or-false statements that affect teacher and student performance; for each, we’ll dive into the details that support the facts, leaving teachers with actionable knowledge that they can put to work right away.

True or False? Homework should be given every night, as this routine promotes learning.

Answer: False! Nightly homework is unnecessary—and can actually be harmful.

Homework for homework’s sake, or homework that’s not tied into the classroom experience, is a demotivating waste of your students’ time and energy. The Education Endowment Foundation Teaching and Learning Toolkit puts it this way: “Planned and focused activities are more beneficial than homework, which is more regular, but may be routine or not linked with what is being learned in class.”

How might teachers put this insight into action?

Homework, in itself, isn’t a bad thing. The key is to make sure that every homework assignment is both necessary and relevant—and leaves students with some time to rest and investigate other parts of their lives. Here are four key mindsets to adopt as an educator:

- Resist the traditional wisdom that equates hardship with learning. Assigning constant homework is often tied into the idea that the more rigorous a class is, the better it is. However, according to research from Duke University’s Professor Harris Cooper, this belief is mistaken: “too much homework may diminish its effectiveness, or even become counterproductive.” A better guideline for homework, Cooper suggests, is to assign 1-2 hours of total homework in high school, and only up to 1 hour in junior high or middle school. This is based on the understanding that school-aged children are developing quickly in multiple realms of their lives; thus, family, outside interests, and sleep all take an unnecessary and damaging hit if students are spending their evenings on busy work. Even for high schoolers, more than two hours of homework was not associated with greater levels of achievement in Cooper’s study.

- Remember that some assignments help learning more than others—and they tend to be simple, connected ones. Research suggests that the more open-ended and unstructured assignments are, the smaller the effect they have on learning. The best kind of homework is made of planned, focused activities that help reinforce what’s been happening in class. Using the spacing effect is one way to help students recall and remember what they’ve been learning: for example, this could include a combination of practice questions from what happened today, three days ago, and five days ago. (You can also consider extending this idea by integrating concepts and skills from other parts of your course into your homework materials). Another helpful approach is to assign an exercise that acts as a simple introduction to material that is about to be taught. In general, make sure that all at-home activities are a continuation of the story that’s playing out in class—in other words, that they’re tied into what happened before the assignment, as well as what will happen next.

- When it comes to homework, stay flexible. Homework shouldn’t be used to teach complex new ideas and skills. Because it’s so important that homework is closely tied with current learning, it’s important to prepare to adjust your assignments on the fly: if you end up running out of time and can’t cover all of a planned subject on a given day, nix any homework that relies on it.

- Never use homework as a punishment. Homework should never be used as a disciplinary tool or a penalty. It’s important for students to know and trust that what they’re doing at home is a vital part of their learning.

- Make sure that your students don’t get stuck before they begin. Teachers tend to under-appreciate one very significant problem when it comes to homework: often, students just don’t know how to do the assignment! Being confused by the instructions—and without the means to remedy the situation—is extremely demotivating. If you find (or suspect) that this might be a problem for your students, one helpful strategy is to give students a few minutes in class to begin their homework, so that you can address any clarifying questions that arise.

In order for students to become high academic achievers, they have to be learning in a way that challenges them at the right level—much like the porridge in the Goldilocks story, it’s got to be just right. Homework is a great tool, but it must be used wisely. Part of our role as teachers is to make sure that the time we ask our students to give us after they leave class is meaningful to their learning; otherwise, the stress and demotivation of “just because” homework can be detrimental to their well-being. As the CTTL’s Dr. Ian Kelleher advises, “The best homework assignments are just 20 minutes long, because those are the ones that the teacher has really planned out carefully.” Put simply: quality beats out quantity, every time.

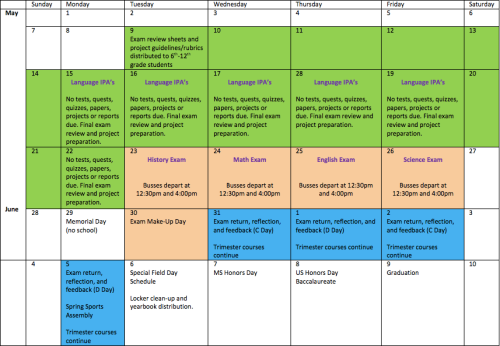

Here at the CTTL, we’re all about quality over quantity. Case in point: our newest endeavor, Neuroteach Global, helps teachers infuse their classroom practices with research-informed strategies for student success—in just 3-5 minutes a day, on a variety of devices.

Neuroteach

Neuroteach

Making Good Progress?

Making Good Progress?

The ABCs of How We Learn:

The ABCs of How We Learn: